The Origins of Matcha

What we now call matcha began as powdered tea mixed with spices—far removed from the refined green elixir we know today. Its origins trace back to Buddhist monks in China during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD). It is the only kind of tea where the entire leaf is ingested. To this end, the leaf is harvested and dried like other tea leaves, and once the leaf veins have been removed, the remaining flakes (i.e. the ‘leaf flesh’ between the veins, today called Tencha in Japanese) are ground into a fine powder, which can be whisked up into a sensational drink with the help of a bamboo whisk.

Matcha Comes to Japan

In the 12th century, monk Eisai travelled to China to study Buddhism, and from his travels brought back more tea seeds (Earlier, monks Saichō and Kūkai had already brought seeds and plants at the beginning of the 9th century) as well as matcha. He presented the matcha to the then emperor of Japan and introduced it to Japanese monasteries, where it was much appreciated for its calming yet alerting effect.

Eisai is said to have planted some seeds on Mount Sefuri and to have gifted some to Myōe Shōnin, who cultivated them near a temple in Uji. Uji translates as “home”, and the region indeed became home to excellent Japanese tea. Today, more than 800 years later, Uji still produces some of the best and most revered Japanese teas in the world.

Matcha Is Good for Monks, for the Samurai, and for You

From Eisai‘s book “Kissa Yōjōki” (Drinking Tea for Health) we know that matcha was highly praised for its beneficial effects on meditation, focus, and longevity.

In addition to the Zen monks, the samurai warriors also discovered its positive effects. It helped them to sharpen their focus, and they are said not only to have drunk it before but also during battle (though one wonders how). Thus, many elements of the Japanese tea ceremony (mainly shaped into a ceremonial ritual by Sen no Rikyu during the 15th/16th century and spread by Japanese tea schools) have roots in Buddhist and samurai traditions.

Matcha Becomes a Japanese Speciality

Curiously enough, the Chinese appear to have forgotten all about matcha. A major difference today between Chinese and Japanese teas is that in China dry heat (wok, indirect fire) is applied to the freshly plucked leaves, while the Japanese use steam (and usually leaves are steamed for a shorter period in and around Kyoto than in other areas of Japan). While the Japanese refined their technique, the Chinese stopped steaming their leaves — with the result that today quality matcha only comes from Japan.

Outside Japan, matcha used to be quite a mystery. Especially in the West, we failed to appreciate the effort that goes into a tiny cup of tea (60ml) with an insane amount of well-practised perfection and ritual pomp. We failed to understand, for example, why it is worth the effort and why your guest would appreciate it if you used a bamboo whisk made by Tango Tanimura-san, who is a 20th-generation whisk maker and whose lineage may reach back to Sen no Rikyu.

Matcha Is a Mystery to the West, but then Someone Frivolously Added Sugar and Milk

Before the year 2020, an often-heard complaint in the Japanese tea industry was that people outside Japan hardly drank any Japanese tea, and that young Japanese people were not overly interested in Japanese teas (apart from ‘iced tea’, which in Japan is not sugared !), let alone in the work on the tea fields. Tea farms were often family-run, and the tea farmers themselves often mentioned that it was a heavily declining trade. The average age of your Japanese tea farm manager is said to be around 70 !

Then came covid, and then in the West – most certainly to the bemusement of Japanese tea drinkers, who feel the West has missed the point entirely – somebody had the frivolous idea to mix milk with ice and sugar, and to top it up with whisked matcha, and now the whole world drinks Matcha Latte.

To add insult to injury, people in the West often dub a matcha latte simply a matcha. So often, in fact, that when somebody orders a matcha in Switzerland, they expect a matcha latte and will be disappointed if they are served a (real) matcha because matcha without milk is still a mysterious drink to many.

Ceremonial Matcha vs. Low-Quality Matcha

Let’s state it clearly here: There is a marked difference between a Matcha (60ml of water, 2 Japanese teaspoons of ceremonial-class matcha powder) and a Matcha Latte (Large glass of milk, generous amount of sugar, a small quantity of low-quality or no-quality powder — plus more crazy condiments such as strawberries or cherries).

The problem is that the whole world now drinks matcha or matcha latte with matcha. So much so that there is not enough matcha to go round. To make matters worse, the tea farmers cannot simply tell their tea plants to increase the production of tea leaves. The plants will do their thing, which they have been doing for thousands of years, and they will not boost production simply because there is a matcha latte craze now.

To cut a long story short: There is not enough matcha powder. Once we’ve used it all up, it’s gone, and we need to wait until next year – and there won’t be much more available next year either.

The West Drinks Too Much of the Powder

Some farmers have written to their long-standing customers to apologise that there is not more matcha to be had. (To read the full message from the president of Ippodo: Click here) Some have written to say that next year they will switch from producing sencha to producing more matcha because this is an outstanding business opportunity (especially for an industry that was more and more vanishing).

Some websites allow you to buy 1 or 2 tins of matcha because the Japanese tea farmers would like to share their product with a wide customer base. (For ‘Sazen: Shop Mindfully’ click here)

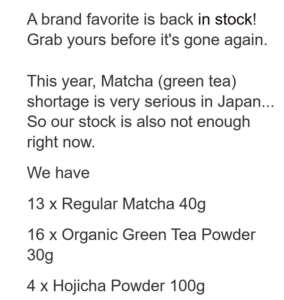

And just as I was writing the above lines, a Japanese start-up wrote to me to inform me that they now had matcha back in stock:

We have 13 tins !

The Result Is Pure Madness in the Tea World

As a consequence, the prices for matcha will go up. The prices for the pre-product (tencha) have already surged by 300%, and this will be reflected in the next round of matcha powder. Furthermore, because many tea farmers try to switch from ordinary tea production to matcha production, there will be fewer leaves made into less ordinary Japanese tea, as a consequence of which the price for sencha, kabusecha, gyokuro and other varieties will also rise. In other words, the West now drinks so much matcha latte that there is not enough for the Japanese themselves and that the price of all Japanese tea is bound to rise. The world’s gone mad.